| « ‘Global Economic Crisis’ exposes plans for a global military dictatorship | "Will the bail-out really matter?" (OpEdNews 404 – Repost) » |

Iran is Not Egypt (Yet)

By Brian M Downing

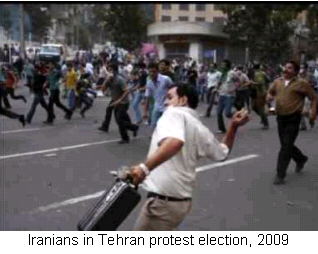

Demonstrations and uprisings against authoritarian rulers are moving across the Middle East. Tunisia and Egypt have driven longtime strong men from office, Libya and Bahrain are in tumult, and Iran is experiencing a return of the demonstrations that took place after the elections of 2009. As much as one might wish to see regime change in Tehran, it might not come nearly as easily and relatively bloodlessly as it did in the Maghreb.

Egyptian leader Hosni Mubarak was an artless figure who over his many years of power managed to alienate a large majority of his subjects. Urban middle classes, rural dwellers, secular intellectuals, and religious scholars could agree on few things in public life, but on the matter of Mubarak's corruption and brutality they could find a great deal of common ground. Further, all could agree that the future did not bode well for young people.

The mullahs who rule Iran, on the other hand, retain a considerable amount of respect from pious sectors of the population. Rural dwellers, merchants, working classes, and others deem the clerics as natural and responsible rulers and as men who delivered the nation from the Shah, Iraqi invaders, and other foreign interlopers. The mullahs, then, hold a measure of legitimacy that Mubarak, though a hero of sorts in the '73 war with Israel, never had.

More than a few mullahs have become quite wealthy since the Shah's rule ended, but this is not a source of public irritation nor is it seen as at the root of the country's economic woes. The economy has indeed suffered as has those in the Maghreb, but many will blame this on foreign sanctions, not on domestic leaders.

Iran showed its capacity to repress demonstrations two years ago and it is uncertain that anything has changed. Its security forces and Revolutionary Guard Corps are not conscripts who reflect the public, they are voluntary. From its special forces down to the Basij militia, the IRGC is heavily indoctrinated and prone to view the demonstrators as privileged and ungrateful urban dwellers with little regard for the nation.

Demonstrators were, and are, seen as dupes of British, American, and Israeli intrigues – charges which resonate in Iranian culture but which had no credibility in Egypt. Over the last few years Iran has endured bombings, assassinations, insurgencies, all of which are clearly the work of outside forces. And of course the international sanctions that are causing rising prices and stagnation call for no inference or speculation as to their origin.

A government with canonically-based certainties as to right and wrong, abiding concerns about foreign forces, substantial support from pious strata, and motivated security forces may well respond to demonstrators far more swiftly and pitilessly than Mubarak or even the Shah dared to.

We might do well to see the Iranians more in light of the Shias of Iraq who were urged to rise up but who then found no foreign help as they were being crushed. The cause of reform in Iran is a long-term one and it must look to building up civil society groups and communicating with non-IRGC parts of the military.

One similarity between Egypt and Iran might become more apparent in coming weeks and months – that public uprisings might not lead to the blossoming of representative government. Instead they may unwittingly help the armed forces to come to the fore as national saviors and to consolidate their already formidable positions in the state and economy.

Brian M. Downing is the author of several works of political and military history, including The Military Revolution and Political Change and The Paths of Glory: War and Social Change in America from the Great War to Vietnam. He can be reached at: