| « Italian Fascism: An Interpretation | Human Security and its Dimensions » |

China’s Belt and Road Initiative – Good for Trade or Debt Diplomacy?

Cathy Smith

China weathered the current political and economic upheaval of Belt and Road Initiative: Catalyst for Global Development or Vehicle for Neo-Colonial Control? The Silk Road of the Ancients (2nd century BCE-15th century CE) and China's BRI have one thing in common: the desire to unite East and West for trade, cultural exchange, and political influence. Structurally, in scope, and by purpose, they are very different.

Ancient Silk Road: Purpose: This was hugely for the purpose of serving as a trade route for silk, spices, and other goods that helped in the cultural exchange between China, Central Asia, the Middle East, and Europe.

- Structure: A network of overland and maritime routes, generally crossing perilous territories, operated by independent traders and different empires.

- Impact: It allowed for the exchange not only of goods but also ideas, religions like Buddhism, and technologies. It was a slow and fragmented system that allowed for both positive and negative interactions between diverse civilizations.

- Power Dynamics: It was less about one power imposing its will; various empires, such as the Han, Parthian, and Roman, had varying degrees of control over parts of the route.

BRI in Modern Times:

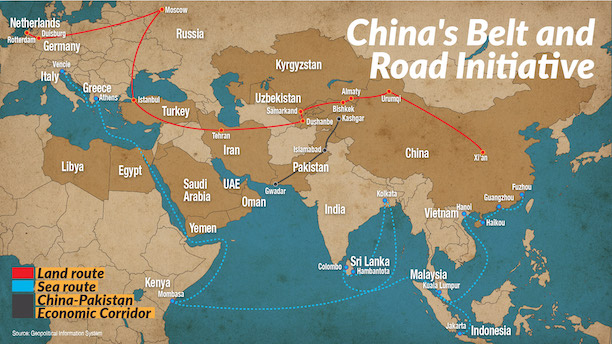

Overview: Announced in 2013, the BRI was a blueprint for redesigning and building a number of infrastructures around the world—roads, railways, ports, and pipelines that would finally connect Asia, Africa, and Europe—facilitating trade and amplifying China's geopolitical influence at large. This is a top-down project driven by a state and headed and solely funded by Chinese SOEs based on loans against investments in different infrastructures.

Impact: Designed to accelerate the pace of economic growth in the developing regions, the initiative has been criticized for encouraging debt dependency and increased Chinese influence in recipient countries. This is a modern infrastructure orientation and not a cultural or intellectual exchange of goods.

Power Dynamics: While the Silk Road was comparatively a shared area, the BRI has increasingly raised one-dimensional concerns about economic dominance by China and thus has been seen even as a tool for neo-colonialism—a conduit offering leverage to the Chinese government vis-à-vis the participating country.

Key Differences:

- Control: The Silk Road was highly decentralized, with the different parts being controlled by different empires, while the BRI is highly centralized; in most projects, the influence of China cannot be overstated.

- Technological Focus: The Silk Road focused on trade goods, whereas the BRI focuses on infrastructure and investment.

- Geopolitical Motive: While the Silk Road was about cultural exchange, the BRI is both an economic development tool and the blueprint for China's expanded global influence.

While the rare routes of trade and connectivity, the former was intercultural in nature, whereas the latter is a modern state-driven initiative, aiming to raise the status of China on the world stage at reshaping international infrastructure.

China's sprawling, ambitious vision to reshape global trade, finance, and infrastructure, the Belt and Road Initiative, is one of the most ambitious plans ever. Launched in 2013, the BRI promises billions in investment, linking Asia, Europe, and Africa with a web of roads, railways, ports, and pipelines. But as China's finance reaches every corner of the globe, the initiative has become mired in controversy: a transformative force for global development, or neo-colonialism reborn? Some critics see the BRI as more about economic control than assistance, while others view it as a much-needed solution to infrastructure deficits in developing regions. Yet the reality is considerably more complex and nuanced, dependent on local contexts and the balance of power in the particular project.

The Neo-Colonialism Case

Debt-Trap Diplomacy

The catch-all criticism of the BRI is "debt-trap diplomacy." Chinese loans to Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Djibouti are commonly marshaled as proof of a more excellent strategy to embed Chinese influence. For instance, when Sri Lanka couldn't pay its loans to build the Hambantota Port, it was forced to let China lease the same facility for 99 years, with the latter having a large infrastructural facility right along the Indian Ocean. It sounds like a warning signal that this type of deal questions whether it's development or just political leverage that China's investments offer using indebtedness. The story of Sri Lanka, as indeed reflected by countries like Pakistan with its Gwadar Port, shows that the BRI could be less about the roads and bridges than locking in Chinese dominance over key global trade routes.

Lack of Transparency and Corruption

Transparency is one of the critical issues in much of the sprawling network that the BRI forms. Non-transparency about contracting and procurement processes has perpetuated many charges of corruption and cronyism, especially in the more poorly governed countries. In Kenya, for instance, Chinese firms received no-bid contracts for the central railway from Nairobi to Mombasa; this fueled charges of overpricing and triggered local disgruntlement. Without open accountability in these projects, serious questions arise about whether such investments are for the public good or a mere pathway to consolidate power and secure lucrative deals by China's state-owned companies. In places like Myanmar and Malaysia, where political regimes can be fragile, such practices deepen inequalities and increase dependence on China, fueling perceptions of neo-colonial exploitation.

Political Leverage and Sovereignty

In the more politically sensitive corners of the BRI, China's influence is often seen as a way to flex soft power over nations that might already be struggling with political instability. In Africa, countries like Zimbabwe and Angola, which have turned to China for support, are now deeply enmeshed in China's economic orbit. While China's loans and infrastructure projects offer much-needed relief, they also come with strings attached. Countries like Zambia, for instance, are becoming increasingly dependent on Chinese loans. In return, China is asking for debt forgiveness to gain control of critical assets. To China, this relationship is an economic investment and a geopolitical influence multiplier. Critics say that China has lost sovereignty and that a country would lose its independence due to being highly economically tied with it.

Environmental and Social Costs

The pace of construction has created jobs - as in CPEC in Pakistan or the Mombasa-Nairobi railway in Kenya - and often at an environmental cost: in Laos, a small, landlocked nation in Southeast Asia, a high-speed rail line is under construction, linking the capital Vientiane to China, amid protests over deforestation and disruption to local ecosystems. In Myanmar, for example, massive dam projects financed by Chinese firms threaten to displace entire communities and divert the course of the Irrawaddy River.

While such projects may yield short-term economic benefits, they can lead to long-term environmental devastation and social chaos. Unless these issues are tackled head-on, the risk is that the BRI will prove a destructive force rather than a development one.

The Case for Global Development

Infrastructure Investment

Notwithstanding criticisms, there is little doubt that the BRI serves a particular and critical need. Many of these countries, particularly those in sub-Saharan Africa and Central Asia, face massive infrastructure gaps that dampen their economic performance. BRI invested in roads, railways, and ports, facilitating trade and regional integration.

Take the example of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, joining the Chinese city of Kashgar with the Pakistani port of Gwadar to reach the massive market of China. Another good example of reducing transport costs, boosting trade, and consequently reaching regional markets is constructing the railway line between Mombasa and Nairobi in East Africa. These projects offer a chance for developing countries to break free from infrastructure bottlenecks that have long stunted their economies.

Economic Growth and Job Creation

The economic benefits of BRI projects are not just theoretical.

More often than not, the economic benefits of BRI projects materialize into tangible benefits for local populations, especially in terms of job creation. In Laos, the Vientiane–Kunming Railway is creating thousands of jobs for the locals, thereby improving labor forces in the country. Similarly, the industrial parks built by China in Ethiopia have started introducing new jobs and increasing wages for the local communities, leading to an improved livelihood.

Where China continues to invest in these projects, the infrastructure can even catalyze broader industrialization that fosters long-term economic growth. The right policies can transform these investments into drivers of local business development, economic empowerment, and corporate autonomy for these nations, offering a hopeful vision of improved livelihoods and economic growth.

Beyond the single countries, the BRI is a vision for a better-connected world.

Its transportation networks, from Central Asia's high-speed railways to East Africa's newly built ports, are supposed to connect far-flung regions with global trading systems. This trade and infrastructure network might unleash profound economic synergies by linking emerging markets with established economies.

The BRI rail links into European places such as Duisburg in Germany, enabling goods to flow from China into Europe and permitting European businesses access to cheaper, faster supply chains. This translates into better access to international markets, more foreign direct investment, and deeper economic cooperation with China and other regional powers for the participating countries.

Access to Finance for Developing Countries

To many developing countries, the BRI has turned out to be a vital alternative to Western-backed financial institutions like the World Bank and the IMF, which more often than not come up with strict preconditions.

But this is where the financing from China comes in; at least, it is far more flexible, with fewer political preconditions.

Tajikistan, which is small and mountainous in Central Asia, with access to capital markets that are deeply limited. As part of BRI, it has arranged to finance desperately needed infrastructure, including a brand-new highway to connect it to China. Without the BRI, it would have left countries like the Republic of Tajikistan, Zimbabwe, and even Greece—nothing but countries that have now turned to China for funding options but to accept Western loans with heavy strings attached. In that sense, the BRI could be viewed as a lifeline to nations desiring to diversify their sources of capital and dependency on traditional financial powers.

Key Considerations and Nuances

Contextual Variability of BRI Projects

The BRI is less of a single-headed monster, a compilation of multiple projects situated in unique contexts. In most cases, specifically within Southeast Asia, the BRI has become a godsend, where its infrastructure and resulting economic benefits were much-needed bridges. Yet, for countries like Sri Lanka and Zambia, for example, the results of the BRI have included negative consequences: increased debt burdens and overdependence on Chinese capital. The impact of BRI projects depends, more or less, on governance structures in the host country and how willing both parties are to negotiate terms. A project works in Malaysia but fails in Myanmar because of the importance of local context.

Improving Governance and Transparency

Speaking of how to make BRI more effective, China should address its issue of transparency.

More transparent contracts, active civil society participation, and deeper consideration of anti-corruption policies would go a long way toward creating trust between China and recipient countries. Governments should, in turn, put in place more stringent regulatory frames to ensure Chinese companies respect local laws and benefit their citizens. As the BRI matures, China can provide a model to inspire good governance practices that deliver prosperity for all.

Sustainable Development and Environmental Integrity

The sustainability of the BRI depends upon its ability to balance development with sustainability in the long run.

If China's infrastructure projects are to create lasting prosperity, they must respect environmental limits and foster social inclusion. Instead, less virulent practices, such as green technologies, environmental impact assessments, and consultations with local communities, are required. The integration of sustainable development into the BRI will serve to protect the environment and, at the same time, provide more credibility for the initiative on the international plane.

The Belt and Road Initiative is neither a purely benign force nor a neo-colonialist scheme.

It is a complex, multifaceted endeavor that mixes promise and peril. For countries needing infrastructure and investment, the BRI is an invaluable opportunity for growth. However, without careful governance, transparency, and attention to local needs, the initiative risks being used as a tool of economic domination rather than development. Ultimately, the future of the BRI depends on whether China can tread that thin line between investment and influence so that its infrastructure projects benefit both China and the world.