| « The US Needs To Apologize to Russia | Columbia University’s Nazi Tradition » |

Purist Holocaust Advocacy and Denial of Other Genocides: A Case Study of the Holodomor and Armenian Genocides

Robert David

The Holocaust, the systematic murder of some six million Jews by Nazi Germany in World War II, occupies a singular and unprecedented position in global memory and historical debate. Its dominant position in Genocide discussions has generated an irrefutable story of victimization and hardship.

But more sinister is a trend among some groups that adhere to the exclusive focus on Holocaust memory: denying or downplaying other genocides, namely the Holodomor and the Armenian Genocide. While the actions of Nazi Germany are undoubtedly heinous, this essay argues that Holocaust purists ignore or deny the genocide of Armenians and Poles, Czechs and Ukrainians, despite clear historical fact confirming the designation of all as genocides.

Examining such case studies provides us with insight into how specificized historical accounts can undermine the universal acceptability of genocides.

The Ideological Framework of Holocaust Purism

Holocaust purism is the ideological position that the Holocaust should be the only, unchallengeable event of genocide recognition of modern history. This view not only underscores the uniqueness of the Jewish experience during World War II but also infers the uniqueness of the Holocaust in scale, scope, and systematic intent (Browning, 2017). This purist ideology often manifests itself in intellectual and political discourse, where attention is largely focused on the Jewish victims of the Nazi atrocities, sometimes to the exclusion of other victims of the same regime or to the belittling of other genocides.

For example, some Holocaust lobby groups' histories that are promoted by museums and memorials tend to emphasize Jewish victimhood to the neglect of others, for example, Romani populations or Slavic people (Klezmer, 2014).

In addition, Holocaust purists typically embrace an exclusionary paradigm that forbids the application of the term "genocide" to other events, even when such events exhibit the same characteristics of systematic massacres. This selective amnesia has not only conditioned popular consciousness but also political discourse surrounding genocide acknowledgment worldwide, especially in the case of events like the Holodomor and the Armenian Genocide.

Recent scholarship has also pinpointed the dangers of such an exclusionary paradigm. As Weiss-Wendt (2020) reminds us, the conclusion that the Holocaust was unique in character has the consequence of creating a hierarchy of victimhood, wherein other genocides are perceived as less central or not worth equal attention. This hierarchy is not abstract; it has material consequences for how societies remember and respond to mass atrocities. For instance, the refusal to recognize the Holodomor or the Armenian Genocide as genocides continues to perpetuate a myth that minimizes the suffering of Ukrainians and Armenians, respectively, and denies efforts at trying to find justice and compensation for these communities.

The Holodomor: A Genocide by Starvation

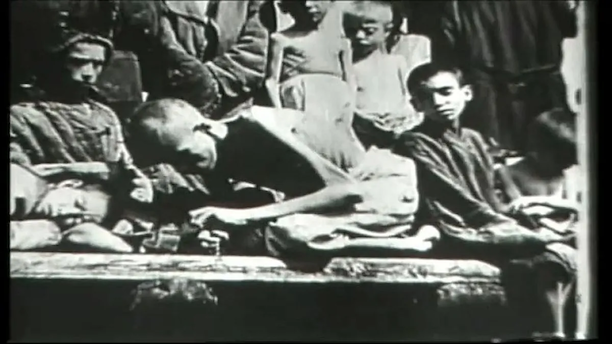

The Holodomor, the artificial famine that killed millions of Ukrainians in 1932 and 1933, has often been at the center of historical dispute. Joseph Stalin's policies in the Soviet Union, including forced collectivization of agriculture and grain seizures, led to mass starvation. The famine has been labeled an act of Genocide intended to wipe out Ukrainian nationalism and resistance to Soviet domination (Applebaum, 2017). The term "Holodomor" itself, derived from the Ukrainian words for "hunger" and "extermination," underlines the very particular intent of the famine as a Genocide instrument.

There are, however, still individuals in denial of the genocidal nature of the Holodomor. Others, particularly in the Russian political arena, continue to play down the famine as a natural disaster, a result of Stalin's economic policies, rather than as an intentional mass extermination policy (Zhukov, 2015). This reductionism is particularly prevalent amongst Holocaust purists, who recoil from the admission of the Holodomor being a genocide for fear of encroaching upon the simplicity of the uniqueness of the Holocaust history and upsetting the simplistic history account of Genocide (Smith, 2010).

Recent research by Marples (2021) has also demonstrated more clearly how the denial of the Holodomor is often tied to geopolitical interests, namely those of Russia. By denying the Holodomor as genocide, Russia seeks to persist with its influence over Ukraine and other post-Soviet countries. Denial is not simply a question of history but an emerging political strategy to subvert Ukrainian sovereignty and national identity.

The Armenian Genocide: A Legacy of Denial

The Armenian Genocide of 1915-1916, committed by the Ottoman Empire, resulted in an estimated 1.5 million Armenians being killed. It is among the most studied genocides but also one of the most politically charged. Despite extensive documentation and survivor accounts, the Turkish government has for years denied the Genocide. This position is sometimes supported by world powers with geopolitical interests in friendly relations with Turkey.

Holocaust purists prefer to focus on the Holocaust rather than on the acknowledgment of the Armenian Genocide, despite the fact that the dynamics of genocide are identical-mass deportations, organized killings, and deliberate destruction of the cultural and social infrastructure (Akçam, 2012).

Denial of the Armenian Genocide has a partially voluntary component, as it stems from a voluntary need to maintain the narrative of Jewish suffering, since acknowledgment of the Armenian Genocide tends to jeopardize the concept of the Holocaust as the "most important" Genocide of the twentieth century (Zhukov, 2015). For instance, pieces such as those found on The Bridgehead do stress the issue of Christian persecution but tend to fail to relate it to the overall framework of Ottoman and Soviet policy, instead focusing on the assumed uniqueness of Jewish victimhood within the Holocaust (The Bridgehead, 2018).

Despite the tremendous academic consensus concerning the Armenian Genocide, holocaust purists and their partisans still refute labeling the Genocide, primarily in political speech and public debate. In this way, Armenian Genocide denial represents a more widespread reluctance to dispute the supremacy of Holocaust remembrance, although this distorts the historical fact.

Suny's (2020) recent study has also addressed the global politics of denial of the Armenian Genocide. States such as the United States have not been eager to officially recognize the Genocide due to their diplomatic relations (Istanbul Nuclear Air Force Base) with Turkey. The studies are often promoted by Holocaust purists, who feel that the recognition of the Armenian Genocide would dilute the singularity of the Holocaust. Such arguments not only maintain historical fallacies but also contribute to the ongoing suffering of the Armenian diaspora, who keep hoping for recognition and justice over the atrocities committed against their ancestors.

Denial of the Holodomor and Armenian Genocide by Holocaust Purists

The Holocaust purists' tendency to deny or minimize other genocides is not an academic controversy in isolation-it has concrete implications for the official designation of Genocide as a category. The Holodomor and Armenian Genocide, both clearly exhibiting genocidal intent, have been subjected to historical forgetting due to the political and ideological agendas surrounding Holocaust memory politics.

Denial of the Holodomor as Genocide is a blatant demonstration of Holocaust purism-led selective memory. Works like Ukrainian Jewish Encounter reveal how, while certain activism groups considered the Holodomor to be a Genocide, others groups operating within Russian political narratives sought to downplay or deny the event entirely (Ukrainian Jewish Encounter, n.d.). This denial is not based on objective scholarly history but on a desire to protect Russia's geopolitical interests and maintain its hand in post-Soviet countries such as Ukraine.

Similarly, the Armenian Genocide is typically denied by individuals who are not willing to call the atrocity a genocide due to political considerations. History.com provides a comprehensive account of the Genocide and the overwhelming evidence supporting its recognition (History.com, 2023). But the overwhelming majority of Holocaust purists will not go near the question with a ten-foot pole, for fear that accepting the Armenian Genocide will disrupt the "unicity" and "squeaky-cleanness" of the Holocaust. By refusing to discuss the other genocides alongside the Holocaust, the purists are working towards a narrow, exclusionist ideology of genocide recognition.

Ethical and Political Implications of Denying Genocide

The ethical implication of genocide denial is enormous. Denial of the Holodomor and Armenian Genocide not only discredits the historical record but also remains harmful to the survivors and heirs of the victims of these acts. In the case of the Holodomor, denial of it as a genocide is harmful to the Ukrainian national identity and collective memory of the victims. Parallel, denial of the Armenian Genocide remains a thorn in the side of the Armenian diaspora, still searching for acknowledgment of the historical record (Akçam, 2012).

Politically, denial of the genocides complicates diplomatic relations. For instance, Turkey's denial of the Armenian Genocide is an ongoing source of tension in its bilateral diplomatic relations with countries like the United States and Armenia. Meanwhile, Russia's failure to acknowledge the Holodomor put pressure on its relations with Ukraine and other countries that hope to declare the event as Genocide (Applebaum, 2017). The involvement of Holocaust purism in these political narratives only serves to further promote nationalist and geopolitical interests that help keep such recognitions at bay.

The Trouble With Purist Holocaust Promotion

Holocaust purism in its strongest form risks being an ideology that obliterates the recognition of other genocides, such as the Holodomor and the Armenian Genocide. Even though the Holocaust is a reference point in modern history, this one-point focus has the potential to lead to the erasure or denial of other atrocities.

Both Holodomor and Armenian Genocide are tragedies that need to be acknowledged, both for their historical importance and the justice and healing which acknowledgment can potentially provide for survivors and descendants alike. As this essay has demonstrated, denial of these genocides, especially on the part of Holocaust purists, is indicative of a wider pattern of politicization of historical memory and a preference for some narratives over others. In the future, there is a need to embrace a more expansive method of genocide recognition that recognizes the suffering of all those groups subject to mass violence, independent of political or ideological imperatives.

The Armenian Genocide and Holodomor, though separated in time, place, and politics, are as closely linked by their shared heart: the planned extermination of a people through systematic policies of starvation, expulsion, and murder. Both events, eclipsed by the prevailing narratives of the Great War and the Soviet narrative, lay bare before us the shivering machinery of state violence and how ideology, nationalism, and power come to conspire to eradicate entire nations.

The Armenian Genocide (1915–1923), carried out by the Ottoman Empire under the cover of World War I, is widely remembered for its massacres and death marches. Less familiar, however, is the organized destruction of Armenian economic and cultural existence that preceded the physical destruction.

The Adana massacres in 1909, often considered precursors to the genocide, were not only random acts of violence but rather an extension of a larger pattern of state-sanctioned intimidation. The Ottoman state took Armenian property, businesses, and land, redistributing them to Muslim communities as part of a policy of actively attempting to Turkify the empire. This economic displacement was as much a weapon as the swords and bullets of the death squads.

The genocide was also directed against Armenian intellectuals and leaders on a night, April 24, 1915, when hundreds were arrested and executed in Constantinople, severing the community's ability to organize and resist. This method of targeting the elite would ring true later in Stalin's purges, when Ukraine's cultural elites and intelligentsia were likewise annihilated.

The Holodomor (1932–1933), Stalin's man-made famine in Soviet Ukraine, is typically described as a disastrous byproduct of collectivization. It was actually a brutally designed act of terror employed to eliminate Ukrainian nationalism and opposition to Soviet occupation. Less well known is the Black Boards-a Soviet policy of shaming and ostracizing villages that were found not to be sufficiently compliant with grain quotas.

The villages were encircled by troops, deprived of all food, and left to perish, and their names displayed on blacklists to prevent any help from reaching them. The Soviet government also attacked the Ukrainian Orthodox Church, burning churches and persecuting priests, as religion was viewed as a cornerstone of Ukrainian identity. The famine was concurrent with a wave of Russification policies, such as the suppression of the Ukrainian language and culture, similar to the Ottoman attempts to eliminate Armenian identity.

Both genocides were made possible by the complicity of the international community. The Armenian Genocide occurred amidst the chaos of World War I, and world powers largely turned a blind eye. The Holodomor, however, was denied and concealed by Western intellectuals and journalists, some of whom, like Walter Duranty of The New York Times, actively downplayed the famine, calling it "mostly bunk." This denialism allowed both regimes to act with impunity, their crimes hidden beneath mountains of propaganda and geopolitical indifference.

The legacy of these genocides is also remarkably similar. The Armenian diaspora, dispersed throughout the globe, became a living testament to survival and perseverance, maintaining their history and culture in exile. Similarly, the Ukrainian diaspora, both in Canada and the United States, became a vocal voice for recognition of the Holodomor, guarding against the erasure of memory of the famine by Soviet revisionism. Both nations have fought vehemently for acknowledgment and justice, most commonly against repressive elements that seek to erase or de-emphasize their suffering.

By interweaving these threads, what becomes apparent is not just the narrative of two genocides but a more general narrative about the fragility of identity when up against state power. The Holodomor and the Armenian Genocide remind us that genocide is not merely a mass-killing exercise but an erasing, dehumanizing, and cultural-extinguishing process. They force us to confront the ugly truth that these atrocities are not exceptions, but the result of policies deliberately pursued, typically with the tacit complicity of an indifferent world. In remembering these experiences, we also remember not only the victims, but the strength of those individuals who have lived with their experiences, so the world will remember.

References

Akçam, T. (2012). The Armenian genocide: A history. Oxford University Press.

Applebaum, A. (2017). Red famine: Stalin’s war on Ukraine. Doubleday.

Browning, C. R. (2017). The origins of the Holocaust. Cambridge University Press.

History.com. (2023). Armenian Genocide: Facts & Timeline. Retrieved from https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/armenian-genocide

Klezmer, M. (2014). Holocaust memory and purist advocacy. Jewish History Quarterly, 29(1), 45-72.

Marples, D. R. (2021). Holodomor: Causes and consequences of the Ukrainian famine. University of Toronto Press.

Smith, J. D. (2010). The politics of memory: Holocaust memory and genocide denial. Journal of Modern History, 82(4), 893-917.

Suny, R. G. (2020). They can live in the desert but nowhere else: A history of the Armenian Genocide. Princeton University Press.

The Bridgehead. (2018). In history’s bloodiest persecution of Christians, the Russian communists murder millions. Retrieved from https://thebridgehead.ca/2018/05/01/in-historys-bloodiest-persecution-of-christians-the-russian-communists-murder-millions/

Ukrainian Jewish Encounter. (n.d.). Holodomor basic facts. Ukrainian Jewish Encounter. Retrieved March 15, 2025, from https://ukrainianjewishencounter.org/en/holodomor-basic-facts/

Weiss-Wendt, A. (2020). The Holocaust and other genocides: History, representation, ethics. University of Wisconsin Press.

Zhukov, A. (2015). The denial of the Holodomor: A case study in historical memory. Soviet Studies, 56(3), 334-350.

Additional Resources:

Armenian Genocide

1. Akçam, T. (2012). The Young Turks' crime against humanity: The Armenian genocide and ethnic cleansing in the Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press.

- This book provides a detailed analysis of the Ottoman policies that led to the Armenian Genocide, including the economic and cultural destruction of Armenian communities.

2. Kévorkian, R. (2011). The Armenian genocide: A complete history. I.B. Tauris.

- A comprehensive account of the Armenian Genocide, including lesser-known aspects such as the Adana massacres and the targeting of Armenian intellectuals.

3. Suny, R. G. (2015). "They can live in the desert but nowhere else": A history of the Armenian genocide. Princeton University Press.

- Explores the ideological and political motivations behind the genocide, including the role of Turkification policies.

4. Balakian, P. (2003). The burning Tigris: The Armenian genocide and America's response. HarperCollins.

- Discusses international responses to the Armenian Genocide, including the role of the U.S. and other global powers.

Holodomor

5. Applebaum, A. (2017). Red famine: Stalin's war on Ukraine. Doubleday.

- A detailed examination of the Holodomor, including the use of Black Boards and the suppression of Ukrainian culture and religion.

6. Conquest, R. (1986). The harvest of sorrow: Soviet collectivization and the terror-famine. Oxford University Press.

- A seminal work on the Holodomor, exploring the deliberate policies that caused the famine and its impact on Ukrainian identity.

7. Snyder, T. (2010). Bloodlands: Europe between Hitler and Stalin. Basic Books.

- Places the Holodomor within the broader context of Stalinist and Nazi atrocities, highlighting the targeting of Ukrainian nationalism.

8. Graziosi, A. (2009). The Soviet 1931–1933 famines and the Ukrainian Holodomor: Is a new interpretation possible, and what would its consequences be? Harvard Ukrainian Studies, 27(1/4), 97–115.

- An academic article that examines the intentionality of the Holodomor and its role in Soviet policy.

Comparative Genocide Studies

9. Dadrian, V. N., & Akçam, T. (2011). Judgment at Istanbul: The Armenian genocide trials. Berghahn Books.

- Discusses the legal and historical implications of the Armenian Genocide, drawing parallels to other genocides.

10. Jones, A. (2010). Genocide: A comprehensive introduction (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Provides a theoretical framework for understanding genocide, including the role of state policies and international complicity.

11. Kiernan, B. (2007). Blood and soil: A world history of genocide and extermination from Sparta to Darfur. Yale University Press.

- Examines the historical patterns of genocide, including the Armenian Genocide and the Holodomor, within a global context.

Primary Documents and Eyewitness Accounts

12. Werfel, F. (1934). The forty days of Musa Dagh. Viking Press.

- A novel based on the true story of Armenian resistance during the genocide, offering insight into the experiences of survivors.

13. Hryshko, W. (1986). The Ukrainian Holocaust of 1933. Bahriany Foundation.

- A collection of eyewitness accounts and primary documents related to the Holodomor.

14. Duranty, W. (1933). Russians hungry but not starving. The New York Times.

- An example of the denialism surrounding the Holodomor, often cited in discussions of Western complicity.

International Complicity and Denial

15. Power, S. (2002). "A problem from hell": America and the age of genocide. Basic Books.

- Explores the role of the U.S. and other nations in responding to (or ignoring) genocides, including the Armenian Genocide and the Holodomor.

16. Mace, J. E. (1986). The politics of famine: American government and press response to the Ukrainian famine, 1932–1933. Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 1(1), 75–94.

- Analyzes the U.S. government and media's response to the Holodomor, including the role of journalists like Walter Duranty.

Purist Holocaust Advocacy and Denial of Other Genocides: A Case Study of the Holodomor and Armenian Genocides

###

© 2025 www.olivebiodiesel.com